Alive and Innovating: Actors & Human Simulation in Arkansas Healthcare

By: Angie Gilbert, Arkansas Children's Hospital

I am an actor by trade. I have always been proud of the fact that I have been a “successful” actor in Little Rock, Arkansas, meaning I have been able to eke out a living acting in our wonderful, if small, southern capital. I have worked on stage and screen, I am still a voice actor for radio and television commercials, and nearly 25 years ago, I was encouraged to become a standardized patient in a new clinical skills program at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS).

This was an entirely unexpected opportunity to earn some income applying my acting skills in helping med students learn – at least, that was my initial, limited understanding of healthcare simulation. I found the work to be so much broader and so wholly rewarding that I’ve now essentially dedicated my career to it as a Healthcare Simulation Educator at Arkansas Children’s Hospital.

The founding directors at the Clinical Skills Center at UAMS were actors. The program was implemented to provide healthcare students of many disciplines – including medical, pharmaceutical and nursing - realistic patient encounters incorporating simulated patients (SPs) to prepare them for their licensing exams as well as real-world encounters.

Approximately 15 years ago, the program branched out to Arkansas Children’s Hospital (ACH). Within a few years, the ACH branch was adopted by the hospital, and is now known as the Arkansas Children’s Simulation Education Center (ACSEC). Both programs are vast, serving the clinical skills and communication education needs of healthcare learners across the state.

Our particular program at Arkansas Children’s Hospital incorporates the use of high-fidelity infant through adult simulators – also known as manikins - as well as SPs, to hone and reinforce the technical and communicative skills of healthcare professionals from almost every department and every level of experience.

The importance of this program to the ultimate safety of our patient population is more greatly recognized than ever.

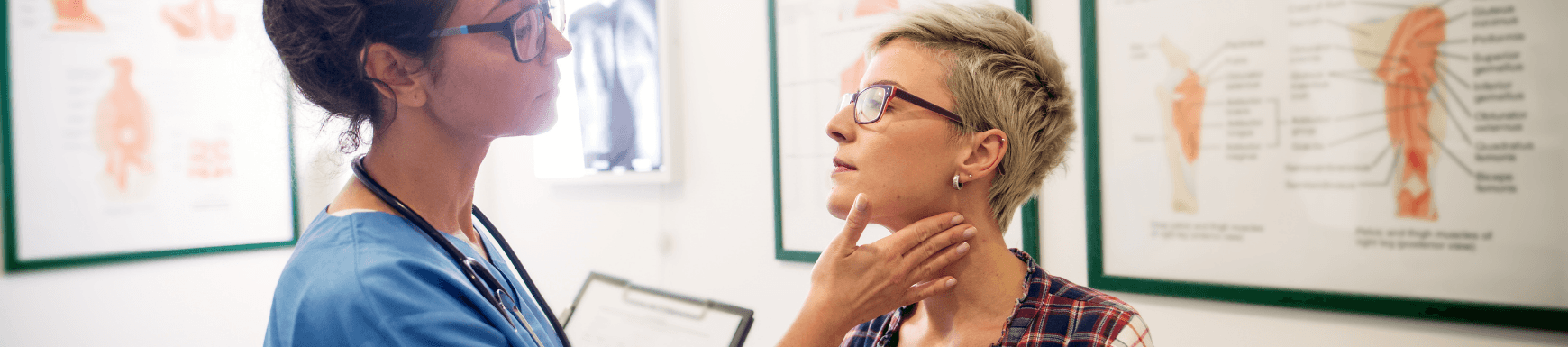

Anesthesiologists at Arkansas Children’s Northwest practice emergency protocol in a sedation module with an SP parent. Photo: Angie Gilbert

Our particular program at Arkansas Children’s Hospital incorporates the use of high-fidelity infant through adult simulators – also known as manikins - as well as SPs, to hone and reinforce the technical and communicative skills of healthcare professionals from almost every department and every level of experience. The importance of this program to the ultimate safety of our patient population is more greatly recognized than ever.

Our program is under the umbrella of Quality and Safety, and our center’s mission is focused around the ACH values of safety, teamwork, compassion and excellence. The program is one of the organization’s many that support Arkansas Children’s efforts to provide CARE (Clinical Care Excellence, Advocacy and Education, Research and Emerging Programs) close to home.

Vildan Tas, M.D., a clinician at the ACH Circle of Friends Clinic and assistant professor in the UAMS College of Medicine General Pediatrics program is one of the creators and course directors of an established ACSEC curriculum.

“I have [had] the privilege to work with the SPs in [the] last 3 years at Arkansas Children's Hospital SIM Center. We run a communication skills curriculum for residents, and it became one of the most valuable experiences they have during their outpatient [rotation],” Tas said. “The SPs are very invested, they live the case scenarios and they even read and learn about the pathologies to act accordingly. They are amazing actors which makes the encounter as natural as it can be in simulation settings, and their feedback from patients' perspectives is precious for our residents. They are a cornerstone of medical education.”

Photo courtesy of ASPEducators.org

An SP does not have to be a professional actor. SPs are most often people who have flexible schedules and are deemed capable of the complex skills required, which include, but are certainly not limited to: clear, non-judgmental communication; memorizing and sometimes improvising details of a case; and what we call the “dual mind” required of an SP, which means being in the moment as the patient they are portraying while also noting important points of an encounter to bring up in debriefing. This debriefing is arguably one of the most important educational components for learners. SPs are often required to provide face-to-face, individual communication feedback for healthcare learners or participate in a larger group debriefing after a simulation, providing observations from the patient or family’s point of view on how the encounter felt emotionally.

Needless to say, extensive training is provided for and required of SPs.

The good news, especially for actors, is that most Arkansas SP programs compensate for all training and events. SPs are hired in the ACH and UAMS programs as contract laborers. Hiring is based on the needs of any given simulation, which, between these two major Arkansas programs, can mean relatively steady work for some. My colleagues and I are quick to explain to new-hires that you cannot expect to pay your rent with SP work, but it can often provide decent supplemental income. Both programs generally rely on word-of-mouth and current SP recommendations in hiring.

Candyce Hinkle, an acclaimed local actor of stage and screen, who has been an SP since the early days of both the ACH and UAMS programs, offers an actor’s insight:

“[I’m] Always hungry to practice my art. Being an SP helps me to conquer my fear of improv. It allows me to improve listening and answering in the most honest voice possible. It gives me an opportunity to develop a whole backstory in preparation of the smallest of encounters. It also gives me the self-satisfaction that maybe, just maybe, I helped someone.”

The evaluations our program receives from the healthcare learners regarding working with SPs is positive across-the-board. The common response we hear involves the value and appreciation of being able to practice with simulated patients before having to encounter real patients, that this practice is extremely beneficial to building confidence. Participants also appreciate learning from the communication feedback offered by the SPs, feedback that rarely is offered in real-world practice.

A simulated patient parent/child pair works with ACH Sleep Center clinicians in practicing a telehealth visit. Photo: Angie Gilbert

I hire actors as SPs for any simulation event, but in particular for cases that require more emotional depth. In a program associated with a children’s hospital, some of our cases must necessarily involve being able to practice communicating difficult news with parents. Actor SPs’ involvement is key in these types of scenarios because actors are often trained and/or have an innate skill of being able to turn emotions on and off.

One of the risks of some human simulation work is endangering SP psychological safety. My colleagues and I try to be hyper-aware of and vigilantly responsive to this safety. When cases require an SP to dive into emotionally taxing subject matter, we have many tools in place to ensure SPs, as well as learners, are psychologically safe in the simulation learning environment. This is an aspect that has become more important for my colleagues and me as we navigate healthcare simulation in the pandemic.

When the world basically shut down in March 2020, healthcare educators were having to radically adjust to keep our important work moving forward. Due to exposure risks, many programs restricted SPs from coming to campus. Many SP cases were then adapted to online platforms such as Zoom. SPs have had to pivot in the ways they fulfill their assignments, too. They have had to be comfortable with sharing their private and safe spaces.

New measures have been implemented to ensure SP psychological safety in remote work environments. While it takes more effort than one would imagine, most of my colleagues and I have been able to successfully do this and keep a portion of our SP pools safe, engaged and employed over the past year.

All of this rapid adjustment to online could not be more timely as the utilization of telehealth in medicine grows, thus the need for simulation practice for telehealth practitioners.

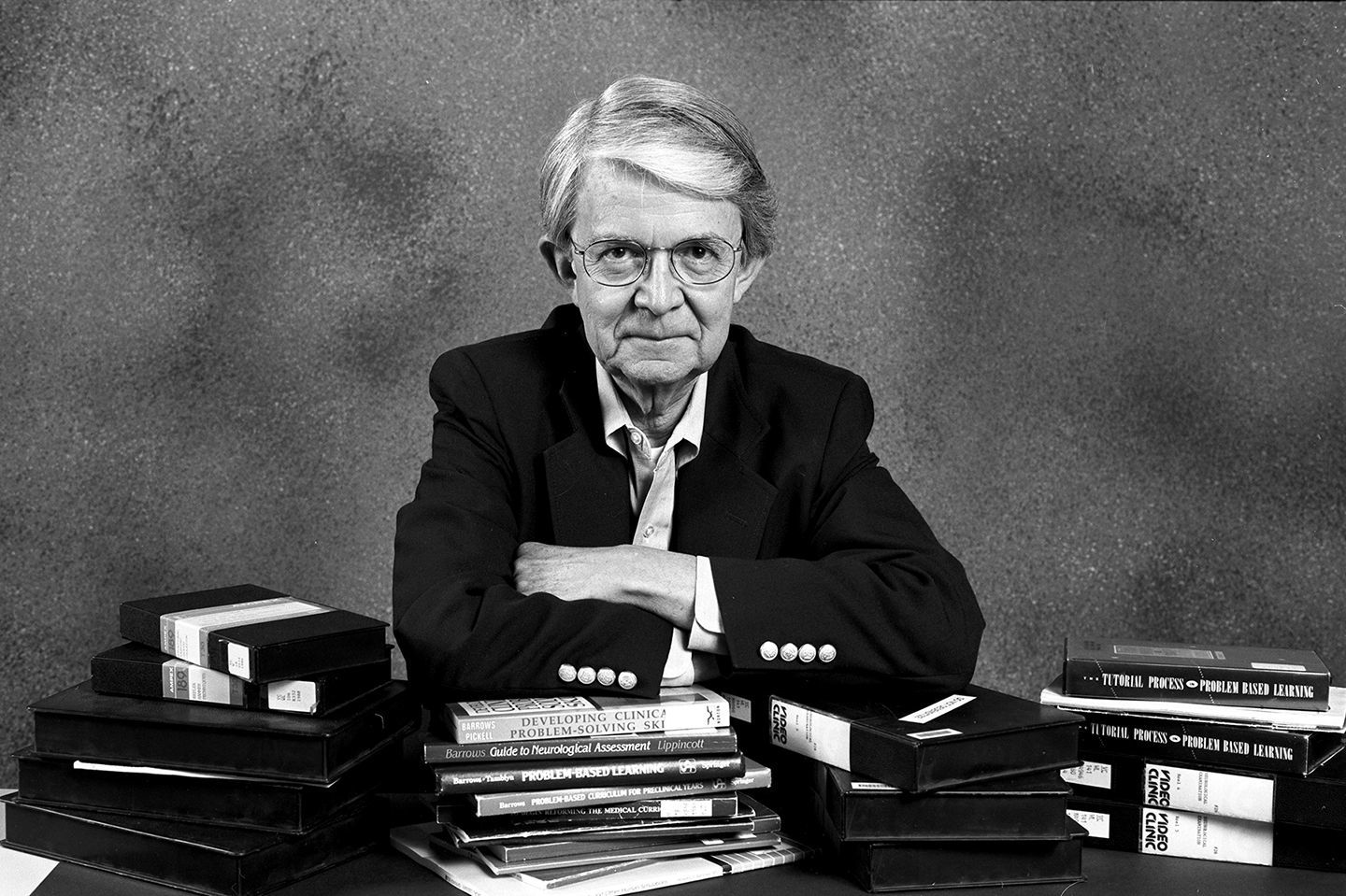

Portrait of Howard S. Barrows by James R. Hawker

Neurologist Howard Barrows, who was Professor Emeritus at the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, is credited with discovering the use of simulated patients in healthcare education in the early 1960s. Simulation programs that incorporate SPs can now be found across the globe.

ACSEC belongs to and regularly contributes knowledge sharing to such international organizations as the Society for Simulation in Healthcare (SSH) and the Association of Standardized Patient Educators (ASPE). Organizations such as these are at the forefront of medical simulation innovation, and the importance of SPs in this innovation cannot be underestimated.

Tools that can measure the economic impacts of human and healthcare simulation in the healthcare industry are only beginning to be developed. Stephen Maloney and Terry Haines, researchers from Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, summarized some of the perceived benefits in their 2016 Advances in Simulation article “Issues of Cost-Benefit and Cost-Effectiveness for Simulation in Health Professions Education”:

A financial benefit in simulation education may be the cost averted through students making fewer errors in real patient situations. Benefits like these that can be monetized can be included in the cost side of a cost-effectiveness analysis. Less tangible benefits may include improved patient-centered care, increased empathy, and a greater understanding of the clinical relevance of the skills and knowledge being taught, influencing future learning experiences [1].

The personal economic benefit for actors, of course, is supplemental income. The reward of using your talents to have a direct impact on improving patient care - take it from an actor like me - is immeasurable.

For information about the SP program at Arkansas Children’s Hospital, please contact Angie Gilbert at gilberta1@archildrens.org.